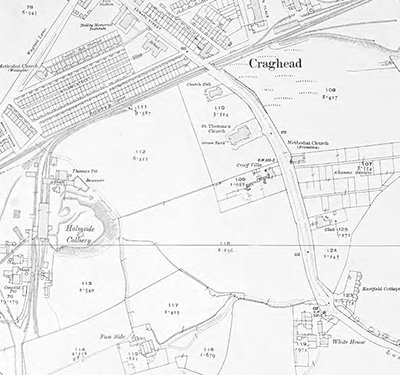

Craghead – Railway Street and Wylam Street

Craghead in 1915

Craghead in 1915

Craghead in 1915

The street names, including ‘Wylam Street’, ‘William Street’ and ‘George Street’, all hint at the area’s mining heritage.

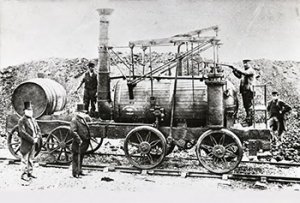

Wylam Dilly

One of the world’s oldest surviving locomotives, Wylam Dilly was once at the cutting edge of steam technology. The precise date of invention is disputed, but was about 1813. The engine was named after Wylam Colliery, where it was built. ‘Dilly’ was a colloquial name for a coal wagon.

It was the brainchild of William Hedley (1779-1843), who worked as a viewer at Wylam Colliery. Previously, locomotives had run on racked rails with a toothed track between the outer rails that pulled the train along like a cog. It was thought to be impossible for engines to run on just the smooth outer rails, but Hedley was convinced that it could be done. His two engines, Wylam Dilly and Puffing Billy, proved him right.

William Hedley went on to manage collieries throughout Northumberland and Durham. His family also owned the mines at South Moor and Craghead.

The Wylam Dilly was put to work in Craghead from 1862 to 1879. In 1882, it was gifted to the National Museum of Scotland. A working replica of Puffing Billy, Wylam Dilly’s sister engine, can be seen nearby at Beamish Museum.

Further information on the Hedleys’ South Moor collieries can be found on the South Moor Heritage Trail and at www.southmoorheritage.org.uk.

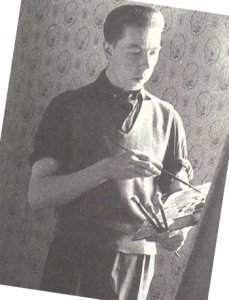

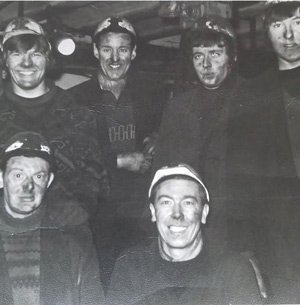

Tom Lamb (1928-2016)

Born in Pelton in May 1928 to William and Jennie Lamb, Tom first discovered his talent for drawing as he recovered from a bout of diphtheria. Soon afterwards, he started work in the Busty Pit at Craghead and continued drawing, taking his sketchbooks to work with him. Some of these sketches were later used to create oil paintings.

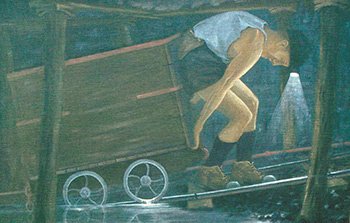

His work captures the harsh and brutal reality of life as a coal miner in convincing detail. The tools, clothing and conditions are vividly portrayed, giving a strong sense of life as a miner in the days before nationalisation, when coal was dug by hand without the aid of mechanical tools.

Tom continued to work at Craghead Pit until it closed in 1969. In later life, he worked on his sketches, turning many into oil paintings and holding exhibitions of his work, which became increasingly important as coal mining declined and fewer people remembered the reality of working underground.

But he was never a commercially minded artist and was more concerned with his subject than any profit or fame that painting might bring him. He later said, “it was the greatest and most monumental experience portraying my fellow miners as they toiled with strained, clenched muscles in the dignity of physical labour in the dark, wet and dangerous conditions underground”.